Amidst the Pursuit of Meaning: The Wane of Velvet Hours

These entries have been compiled from the marginalia, letters, and encrypted journals of Nepher Roux, a time traveler whose sense of nostalgia spans several centuries and at least two futures. Each chapter stands as both a memory and a distortion

Chapter 2

The Wane of Velvet Hours

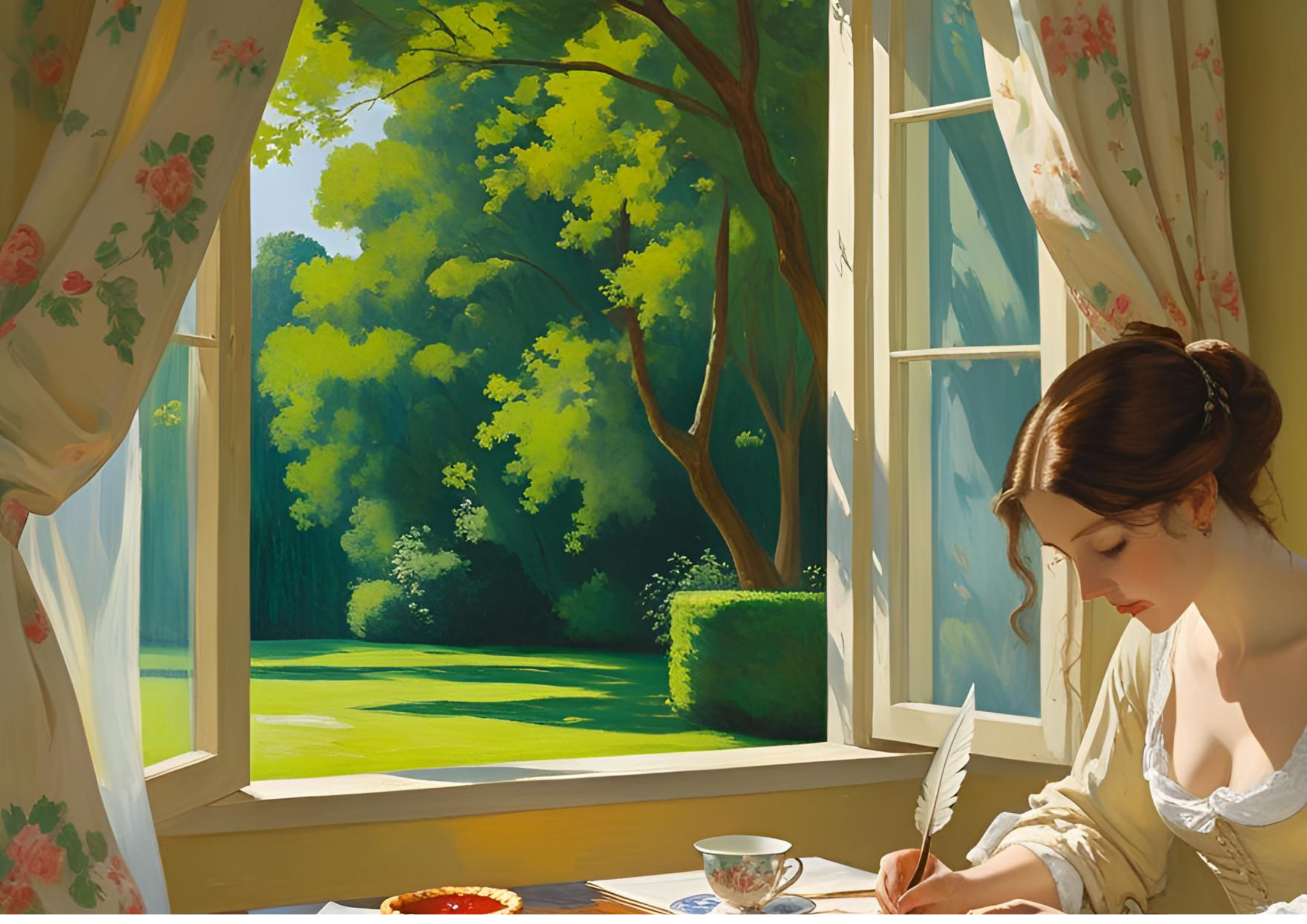

There are evenings that seem to unspool without gravity—those dusklit interludes where memory and presentiment intermingle like shadow and perfume. In such an hour, I recall the winter salons of Vienna in the 1780s, where candlelight slid languidly across parquet floors and the clink of porcelain demitasses was almost orchestral. I was then Madame Roux of the Rue Tuchlauben, allegedly widowed (and conveniently so), a woman of indeterminate age but practiced gaiety, known among the polymaths and melancholics who haunted the smoke-coiled evenings.

They called me “La Finnoise,” and though the name was exoticized beyond recognition, it suited the person I was playing—aloof, elliptical, draped in silk and affectation. Yet beneath the sapphire velvet and powdered coiffure was the child who once scraped frost off her mother’s window with the back of a spoon, watching the moonlight cleave through the pine forest.

It is strange how the past never obeys chronology. I find that the Helsinki of my girlhood now bleeds into Mozart’s Vienna, and that both are haunted by the lemon trees of Alexandria, where I lived (or rather, was detained by my own fascination) during the late 1920s. I wore linen then, and my skin remembered the sun like a private scandal. The conversations in Alexandria were endless, scented with cardamom and empire. We debated time as though it were a negotiable substance. I often remained silent, knowing better.

What persists, what truly binds these epochs together, is not the architecture or the fashion, though I adored both and curated them obsessively—it is the ache. The ache of being unmoored. Of remembering too much. Of having no fixed death to arrange one's life around.

So many of the people I loved—truly loved—exist now only in the marginalia of my journals. A man in Vienna who taught me to waltz using only shadows. A girl in Helsinki whose laugh made the crows quiet. A scholar in Alexandria who believed he had deciphered a universal script and vanished before breakfast.

I have learned, reluctantly, that nostalgia is not a longing for the past, but for a version of the self that could feel astonishment without irony. That is the real loss. And perhaps, the real crime of time travel—not that one escapes chronology, but that one must survive the erosion of wonder.

I write this now from an unnamed year. The fashion is anachronistic, the climate confused. But outside, a single birch tree stands beside an orange tree, and for a moment, they coexist, as all my lives do, folded into one another like forgotten letters pressed into a book.

And somewhere, beyond the reach of my recollection, someone is beginning again. Or has just said goodbye.

It was then—mid-sentence, quite literally—that I was interrupted by a low mechanical chime. Not one of my own devising. I have never trusted alarms, clocks, or anything that insists on linearity. But this was not the polite bell of the 18th-century butler, nor the rattle of a pneumatic message tube from my days in pre-war Berlin. No, this was unmistakably modern—or possibly future—though worn with age. Tinny, like a wind-up toy exhaling its last breath.

I rose, somewhat dramatically, from my writing chaise (a gift from an ill-fated Spanish marquis, long decomposed), and padded toward the front vestibule of my current residence—a nondescript row house that pretends to be Edwardian but is riddled with inconsistencies, much like myself.

There, waiting on the doormat, was a small, cloth-bound parcel, tied with string. The handwriting was my own.

I hesitated—not from fear, for fear is a luxury of the inexperienced—but from annoyance. Time anomalies are so rarely punctual.

Opening the parcel revealed three items:

A faded, annotated recipe card for Piirakka Kivimarja—gooseberry tarts, the rustic kind, with rye crust and a smudge of honey at the corner.

A silk glove, left-hand only, with scorched fingertips.

And most curiously, a pressed sprig of vitsaspensas—a flowering shrub extinct in this century, though I distinctly remember cultivating it in the gardens of 2074 Helsinki.

Naturally, I made the tarts. What else is one to do with a temporal puzzle but eat it?

The recipe was in my grandmother’s hand. Or possibly mine, forged for subtlety. The gooseberries had come from nowhere discernible; I found them in a bowl beside the icebox, glistening like small planets. Their taste was exact—sharp, citric, ancestral. They pulled open a memory I had not summoned:

A summer bonfire. Helsinki. Me at fourteen. A boy named Ilari trying to teach me how to throw a rock into a lake so it skips more than five times. I failed. He laughed. I hated him for it—for the ease of his joy. But then he handed me a gooseberry. And I forgave him, entirely.

I stood for a long while in the kitchen, dusted with flour, tart cooling by the window, trying to place the source of the glove and the reason for its scorch marks. I knew that soon I would have to follow the thread—perhaps back to Alexandria, or forward to wherever I had left the glove, or lost the hand.

But not yet.

For now, I write. And eat. And let the present—such as it is—pretend to hold me in place.